- Home

- Norman Mailer

The Spooky Art

The Spooky Art Read online

Copyright ©2003 by Norman Mailer

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

RANDOM HOUSE and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Mailer, Norman.

The spooky art: some thoughts on writing / Norman Mailer.—1st ed.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-1-58836-286-5

1. Mailer, Norman. 2. Fiction—Authorship. 3. Authorship. I. Title.

PS3525.A4152 S66 2003 808′.02—dc21 2002029170

Random House website address: www.atrandom.com

v3.1_r1

TO

J. MICHAEL LENNON

Praise for Norman Mailer

“[Norman Mailer] loomed over American letters longer and larger than any writer of his generation.”

—The New York Times

“A writer of the greatest and most reckless talent.”

—The New Yorker

“Mailer is indispensable, an American treasure.”

—The Washington Post

“A devastatingly alive and original creative mind.”

—Life

“Mailer is fierce, courageous, and reckless and nearly everything he writes has sections of headlong brilliance.”

—The New York Review of Books

“The largest mind and imagination at work [in modern] American literature … Unlike just about every American writer since Henry James, Mailer has managed to grow and become richer in wisdom with each new book.”

—Chicago Tribune

“Mailer is a master of his craft. His language carries you through the story like a leaf on a stream.”

—The Cincinnati Post

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

A Preface with Three Warnings and One Apology

Part I

Lit Biz Lit Biz

Writing Courses

The Last Draft of The Deer Park

Best-sellers

Reviews, Publicity, and Success

Social Life, Literary Desires, Literary Corruption

Craft Hazards

Style

First Person Versus Third Person

Real Life Versus Plot Life

Instinct and Influence

Stamina

A Coda to “Craft”

Psychology Legend and Identity

Living in the World

Mind and Body, Ego and Work

Gender, Narcissism, Masturbation

The Unconscious

Philosophy Primitive Man, Art and Science, Evil and Judgment

Attacks on Reality

Social Vision

Moral Vision

Being and Nothingness

Miscellany: Pornography, Picasso, and Aphorisms

Part II

Genre Genre

Journalistic Research

Television

Film

The Occult

Giants Tolstoy

Huckleberry Finn—Alive at 100

Oddments on Hemingway

The Turd Test

D. H. Lawrence

A Lagniappe for the Reader

The Argument Reinvigorated

Acknowledgments

Source Notes

About the Author

By Norman Mailer

He lived at a little distance from his body, regarding his own acts with doubtful side-glances. He had an odd autobiographical habit which led him to compose in his mind from time to time a short sentence about himself …

James Joyce, “A Painful Case”

I was never so rapid in my virtue but my vice kept up with me. We are double-edged blades, and every time we whet our virtue the return stroke straps our vice.

Henry David Thoreau, Journals

A PREFACE WITH THREE WARNINGS AND ONE APOLOGY

During the seven years I worked on Harlot’s Ghost, I perceived the CIA and its agents as people of high morals and thorough deceit, loyalty and duplicity, passion and ice-cold detachment. So many writers, including myself, have a bit of that in our makeup. It is part of what has made us novelists, even as intelligence agents are drawn to their profession by the striking opposites in their natures.

Let me assert from the outset, however, that The Spooky Art is not a book about intelligence agents. A work of that sort I might call The Art of the Spooks. This book, however, as the subtitle states, is about writing, its perils, joys, vicissitudes, its loneliness, its celebrity if you are lucky and not so very lucky in just that way. Needless to add, it speaks of problems of craft and plot, character, style, third person, first person, the special psychology of the writer. (I do not think novelists—good novelists, that is—are altogether like other people.) We novelists, good and bad, are also closet philosophers, and one is ready therefore—how not?—to offer one’s own forays into the nature of such matters as being and nothingness, the near-to-unclassifiable presence of the unconscious and its demonic weapon—writer’s block. En route, one looks into the need for stamina in doing a novel, and the relation of stamina to one’s style. There are discussions of the differences and similarities between fiction and history, fiction and journalism, and, of course, I have often thought about the life of action and the life of meditation as it affects one’s work. I have talked and written about the pitfalls of early success and how to cope with disastrous reviews and how we each do our best to live with the competitive spirit of the novelist rather than be eaten out by it. There is talk about identity and occasional crises of identity, as well as the presence of the unconscious in relation to the novelist, taken together with such strategems as when it is wise to enter a character’s mind and when it is unwise to make characters out of real people in one’s life.

All of that is Part I of this book. Part II concerns Genre and Colleagues. Since writers are often in search of how to work in other arts and crafts, Genre has to do with film and painting and journalism, with television and graffiti, as examples of some of the ways and by-ways down which writers search and/or flee from their more direct responsibility.

Finally, there is another section at the end called Giants and Colleagues, filled with a mix of thoughtful and/or shoot-from-the-hip candor about some of my contemporaries, rivals, and literary idols, as well as a few pieces of more formal criticism. Among the authors discussed, some in reasonable depth, others in no more than passing comment, are Hemingway, Faulkner, Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy, Updike, Cheever, Roth, Doctorow, Capote, Vidal, Bellow, Heller, Borges, James Jones, Styron, Chekhov, James T. Farrell, Henry Adams, Henry James, García Márquez, Melville, Proust, Beckett, Dreiser, Graham Greene, William Burroughs, Scott Fitzgerald, Nelson Algren, Kurt Vonnegut, Dwight Macdonald, Toni Morrison, Thomas Wolfe, Tom Wolfe, Jean Malaquais, Don DeLillo, Henry Miller, John Steinbeck, Christopher Isherwood, William Kennedy, Joan Didion, Kate Millett, Jonathan Franzen, Ralph Ellison, Joyce Carol Oates, John Dos Passos, D. H. Lawrence, Mark Twain, Freud, and Marx. Even Bill Buckley is mentioned (in relation to character versus plot). And Stephen King for style.

Taken all together, the result—one would hope—is a volume able to appeal to serious writers and to people who wish to write, to students, to critics, to men and women who love to read. But most of all, this may be a book for young novelists who wish to improve their skills and their commitment to the subtle difficulties and uncharted mysteries of serious novel-writing itself.

Now, for the warnings. A good deal of hesitation went along with the title. Spoo

ky is virtually a child’s word and seemed too casual. Besides, it does not always apply. Not all days at one’s desk are odd or subtly frightening or, for that matter, full of scary fun. Novel-writing can be dogged. There are unproductive hours that feel like nothing so much as the act of trying to start an old car when the motor has gone dead on you.

Nor is this a geriatric analogy. It is usually young men who have old cars. Moreover, there is no sense of youth that a young man can feel on a truly bad day of writing. Young novelists do get to feel like old men on such unhappy occasions, as if whatever talent they once possessed is now gone. The first intimation of old age for many a young novelist is the day when the gift does not appear, or comes through hobbled. Scenes that one expected to be rich are without presence on the page. One’s inner life—that exceptional sense of oneself as possessed of thoughts that are not like others’—is absent. The scene one is working on is as boring as one’s breath on a dull day.

That is the worst, and there is nothing mysterious about such mornings, afternoons, or nights unless it is the new and intimate sense that destiny never guarantees a happy end. You are brought up close, on such occasions, to the future rigor of an unhappy denouement for yourself.

But there are also odd, offbeat, happy days when something does happen as you write and your characters take surprising turns, sometimes revealing themselves to you on the page in a manner other than you expected them to be. You discover that you know more about life and your characters than you thought you did. Such days are glorious. And they are certainly spooky in the most agreeable fashion. You feel close to all the outer stuff!

Of course, no two days of good work are necessarily the same. One may be practical and effective on certain mornings and the skill is actually in the sobriety of the effort. For another kind of hour, one takes risks. Yet if you have gotten good enough over the years (after decades of such varied mornings), there is also the sense of a governing hand (not necessarily and altogether your own) that keeps the highs and the lows from dashing away from one another so outrageously that your novel changes from chapter to chapter. (That is as bad as a car that pops out of gear at the damnedest times.)

All right. The point of this introduction has possibly been made. In any event, I, as the author and assembler of this work, have succeeded in justifying the title to myself.

Let me add, however, a second warning. We have here a reasonably sized volume that will tell you a good deal of what I know about the problems of writing, and more than occasionally, they are advanced problems. So it is not a how-to-do-it for beginners who want basic approaches to plot, dialogue, suspense, and marketing of manuscripts all carefully laid out. This is, rather, a book for men and women who have already found some vocation to write in college or in graduate school, have perhaps taken courses on novel technique, are even advanced students who have begun to encounter the subtle perils and hazards of the writer’s life.

I have also to offer a last warning, which concerns me most. The Spooky Art, by the nature of its sources (which derive from pieces I have written and extracts from interviews I have given), is without stylistic unity. The manner shifts at times from page to page. Given the separate components, there was no way to avoid this. Off-the-cuff remarks in an interview, even when polished to a modicum of good syntax, can hardly be the equal of an essay done at the top of one’s form. Yet the scattered materials of a writer offer just such a spectrum of harsh perceptions roughly stated and insights good enough occasionally to startle even one’s best perception of oneself. I have, however, tried to soften some of the transitions between reworked interviews and more formal essays, and in most places the reader should not suffer too many jolts.

Still, some of you may refuse to treat this as a consecutive work of printed pages so much as an unexpected and possibly dubious gift of chocolates into which they can dip and move on, pleasure alternating with displeasure. I cannot pretend to say this is wrong. I have tried to put some separate elements together with as much order as is possible under these curious circumstances—close to fifty years of reflecting, meditating, musing, and declaring my thoughts on a profession I practiced and could not always feel I understood—but to those readers for whom order in style is one of the cardinal literary virtues (and I am one of them), there may be no other way to treat this volume than as a gift of occasionally exceptional sweetmeats and disappointments. (Nor will every title and subtitle deliver its promise.)

Now, for the apology. By now, at least as many women as men are novelists, but the old habit of speaking of a writer as he persists. So, I’ve employed the masculine pronoun most of the time when making general remarks about writers. I do not know if the women who read this book will be all that inclined to forgive me, but the alternative was to edit many old remarks over into a style I cannot bear—the rhetorically hygienic politically correct.

All this said, I still have a few hopes that the order imposed on these fifty years of opinions and conclusions will be read by some from the first page to the last, and that a few readers will find The Spooky Art to be an intimate handbook they can return to over the decades of their careers.

Here then is a collection of literary gleanings, aperçus, fulminations, pensées, gripes, insights, regrets and affirmations, a few excuses, several insults, and a number of essays more or less intact. May the critics feel bound to debate some of these notions in time to come.

It is interesting that my ceremonial sense intensifies as I grow older, and so I have looked to assemble this book in time for it to come out on January 31, 2003. I will be exactly eighty years old on that occasion. I would hope I am not looking for unwarranted easy treatment by this last remark. Can I possibly be speaking the truth?

PART I

LIT BIZ

LIT BIZ

I am tempted to call this section Economics, for it concerns the loss and gain (economically, psychically, physically) of living as a writer. Let’s settle, however, for a term that may be closer to the everyday reality: Lit Biz. Spend your working life as a writer and depend on it—your income, your spirit, and your liver are all on close terms with Lit Biz.

In 1963, Steve Marcus did an interview with me for The Paris Review, and I have taken the liberty of separating his careful and elegantly structured questions into several parts in order to give a quick shape to my first years as a writer. For those who are more interested in what I have to say about writing in general than about myself in particular, you are invited to skip over these autobiographical details and move on to a few comments on my first two books, The Naked and the Dead and Barbary Shore. Or, if you are in search of directly useful nitty-gritty, move even further, to “The Last Draft of The Deer Park.”

STEVEN MARCUS: Do you need any particular environment in which to write?

NORMAN MAILER: I like a room with a view, preferably a long view. I like looking at the sea, or ships, or anything which has a vista to it. Oddly enough, I’ve never worked in the mountains.

SM: When did you first think of becoming a writer?

NM: That’s hard to answer. I did a lot of writing when I was young.

SM: How young?

NM: Seven.

SM: A real novel?

NM: Well, it was a science fiction novel about people on Earth taking a rocket ship to Mars. The hero had a name which sounded like Buck Rogers. His assistant was called Dr. Hoor.

SM: Doctor …?

NM: Dr. Hoor. Whore, pronounced H-O-O-R. That’s the way we used to pronounce whore in Brooklyn. He was patterned directly after Dr. Huer in Buck Rogers, who was then appearing on radio. This novel filled two and a half paper notebooks. You know the type, about seven inches by ten. They had soft, shiny blue covers and they were, oh, only ten cents in those days, or a nickel. They ran to about a hundred pages each and I used to write on both sides. My writing was remarkable for the way I hyphenated words. I loved hyphenating, and so I would hyphenate “the” and make it “th-e” if it came at the end of the line. Or “the

y” would become “the-y.” Then I didn’t write again for a long time. I didn’t even try out for the high school literary magazine. I had friends who wrote short stories, and their short stories were far better than the ones I would write for assignments in high school English and I felt no desire to write. When I got to college, I started again. The jump from Boys’ High School in Brooklyn to Harvard came as a shock. I started reading some decent novels for the first time.

SM: You mentioned in Advertisements for Myself that reading Studs Lonigan made you want to be a writer.

NM: Yes. It was the first truly literary experience I had, because the background of Studs was similar to mine. I grew up in Brooklyn, not Chicago, but the atmosphere had the same flatness of affect. Until then I had never considered my life or the life of the people around me as even remotely worthy of—well, I didn’t believe they could be treated as subjects for fiction. It never occurred to me. Suddenly I realized you could write about your own life.

SM: When did you feel that you were started as a writer?

NM: When I first began to write again at Harvard. I wasn’t very good. I was doing short stories all the time, but I wasn’t good. If there were fifty people in the class, let’s say I was somewhere in the top ten. My teachers thought I was fair, but I don’t believe they ever thought for a moment I was really talented. Then in the middle of my Sophomore year I started getting better. I got on The Harvard Advocate and that gave me confidence, and about this time I did a couple of fairly good short stories for English A-1, one of which won Story magazine’s college contest for that year.

SM: Was that the story about Al Groot?

NM: Yes. And when I found out it had won—which was at the beginning of the summer after my Sophomore year [1941]—well, that fortified me, and I sat down and wrote a novel. It was a very bad novel. I wrote it in two months. It was called No Percentage. It was just terrible. But I never questioned any longer whether I was started as a writer.

Ancient Evenings

Ancient Evenings The Gospel According to the Son

The Gospel According to the Son Oswald's Tale: An American Mystery

Oswald's Tale: An American Mystery The Castle in the Forest

The Castle in the Forest The Executioner's Song

The Executioner's Song Why Are We in Vietnam?

Why Are We in Vietnam? The Deer Park: A Play

The Deer Park: A Play An American Dream

An American Dream Why Are We at War?

Why Are We at War? The Time of Her Time

The Time of Her Time The Spooky Art: Thoughts on Writing

The Spooky Art: Thoughts on Writing Miami and the Siege of Chicago

Miami and the Siege of Chicago Mind of an Outlaw: Selected Essays

Mind of an Outlaw: Selected Essays Barbary Shore

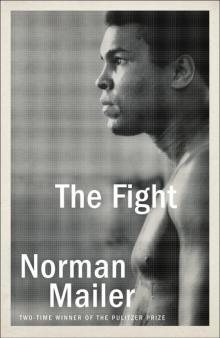

Barbary Shore The Fight

The Fight Harlot's Ghost

Harlot's Ghost Tough Guys Don't Dance

Tough Guys Don't Dance Of a Fire on the Moon

Of a Fire on the Moon The Spooky Art

The Spooky Art The Deer Park

The Deer Park On God: An Uncommon Conversation

On God: An Uncommon Conversation Mind of an Outlaw

Mind of an Outlaw Oswald's Tale

Oswald's Tale